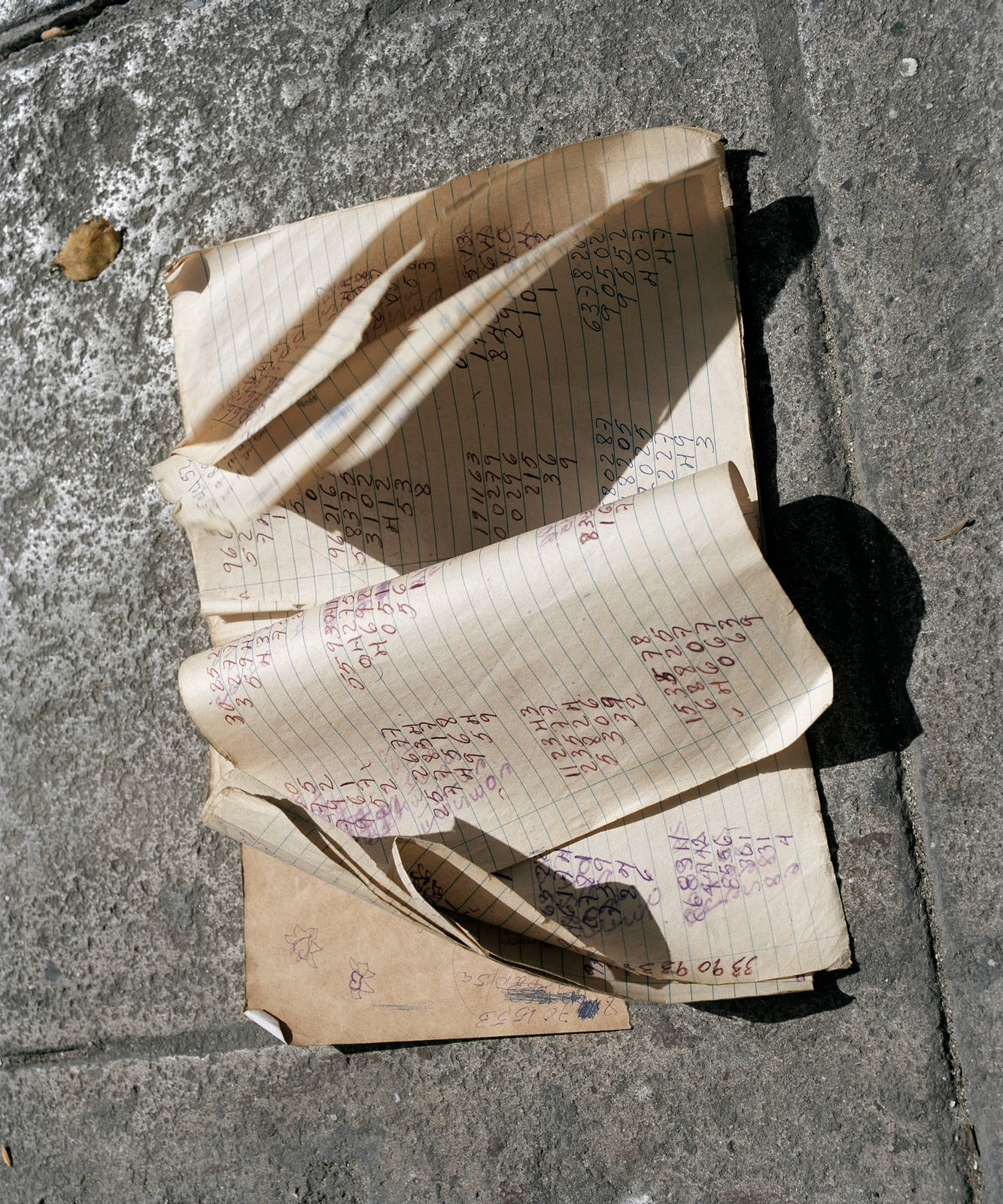

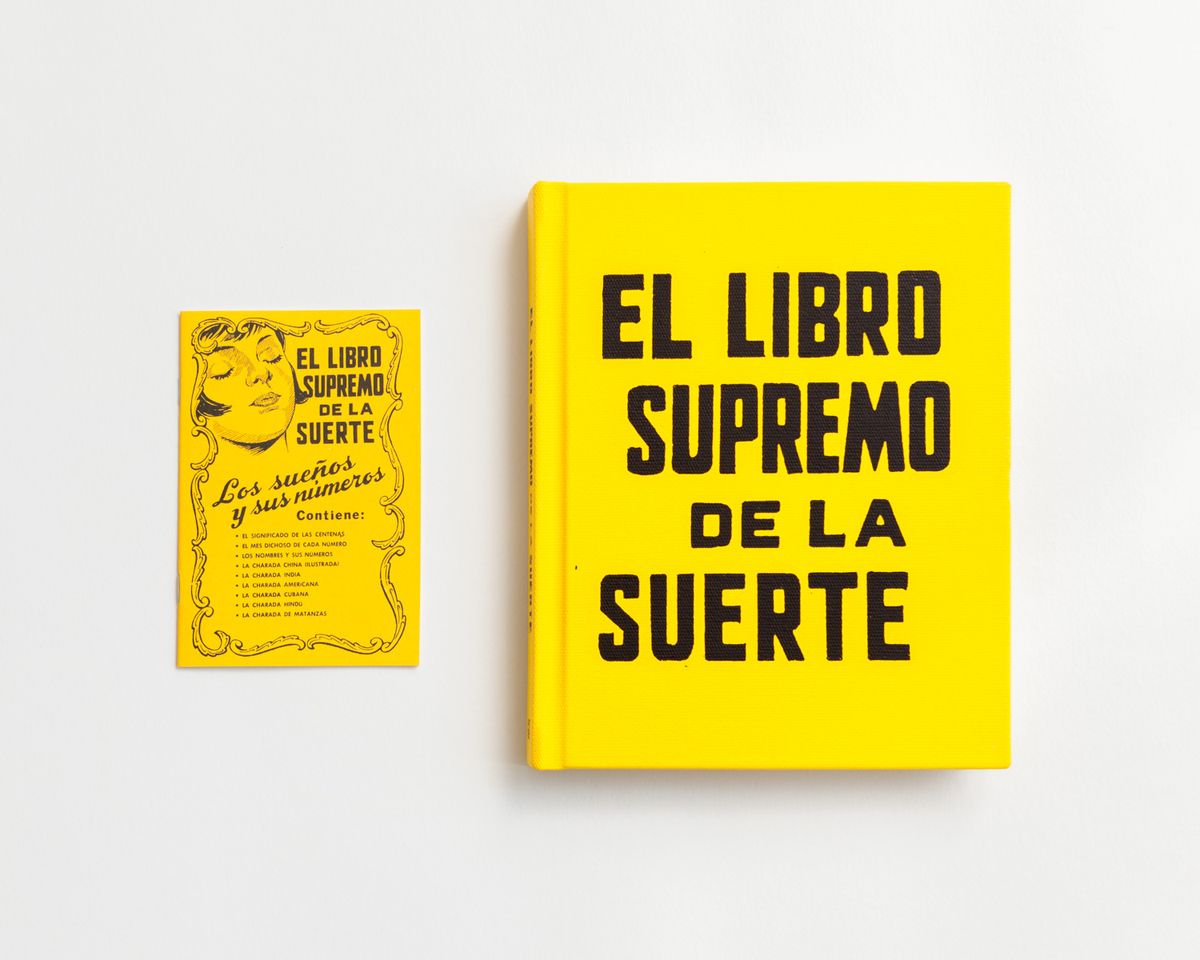

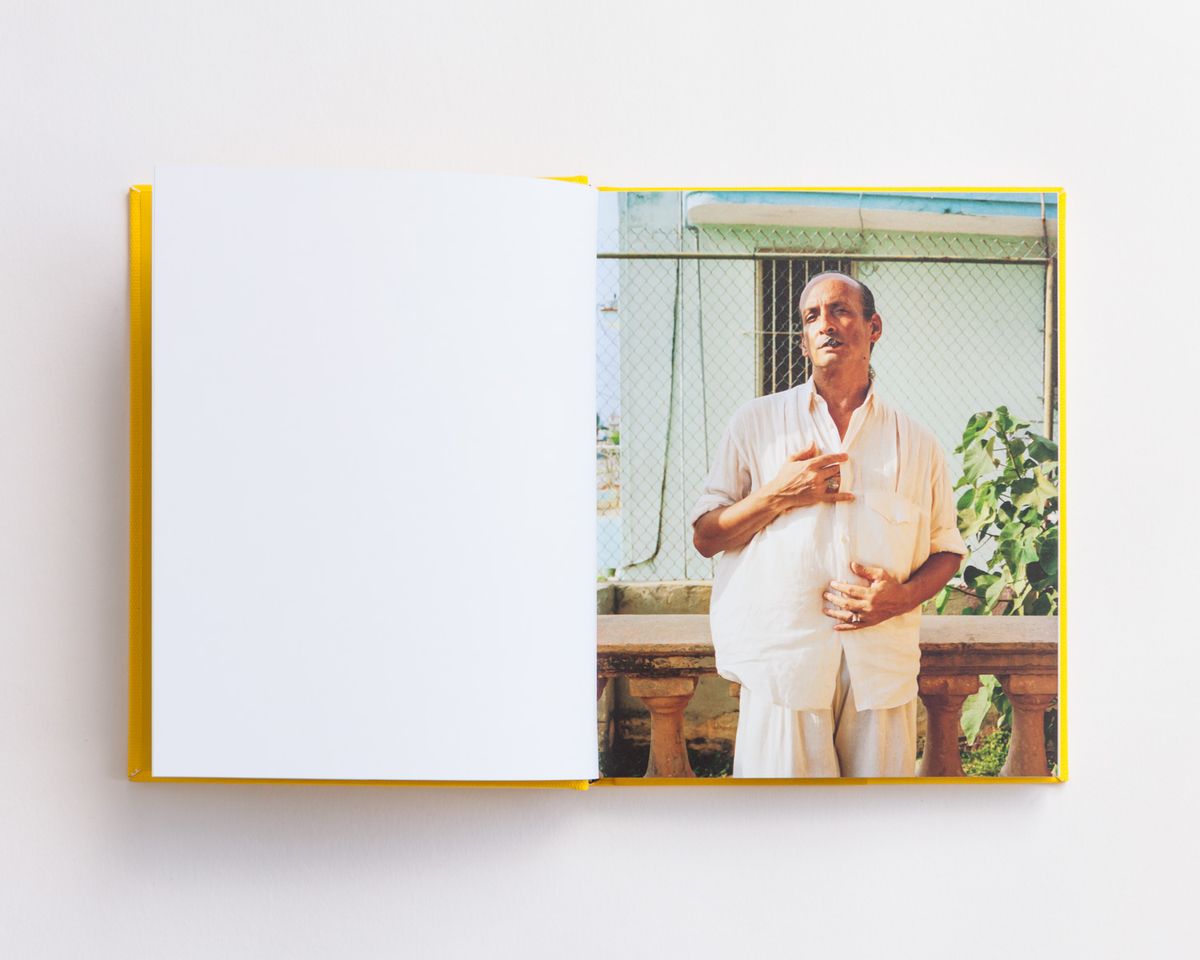

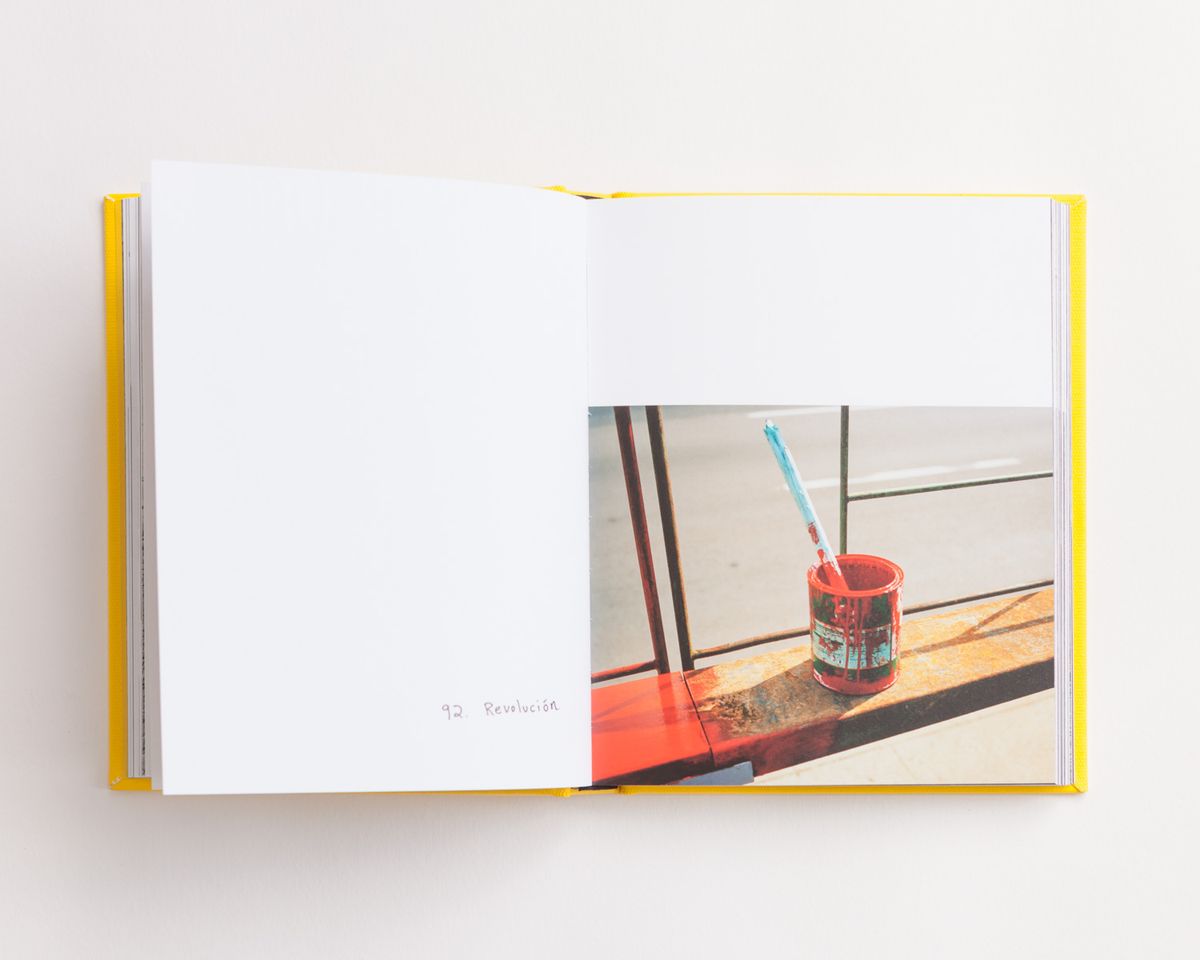

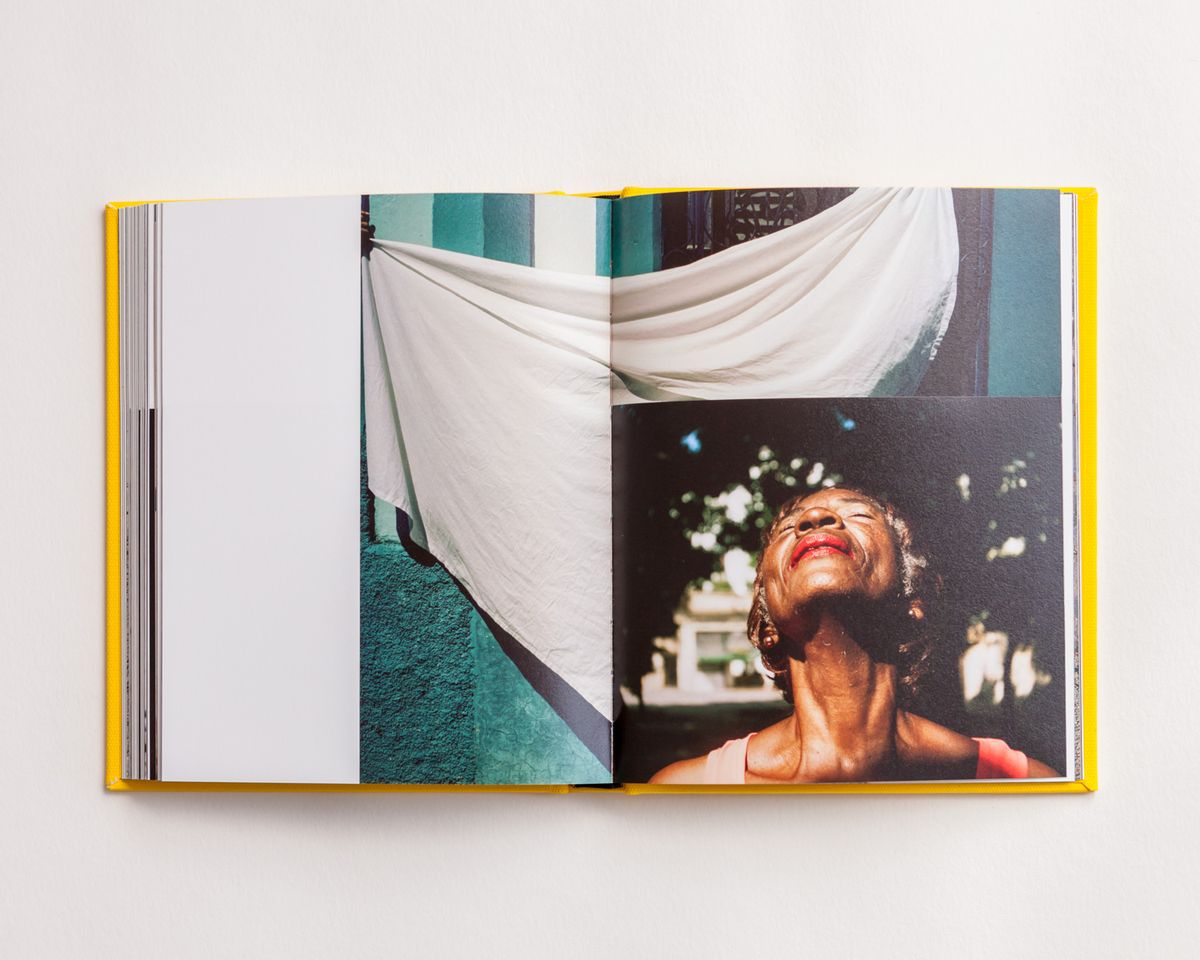

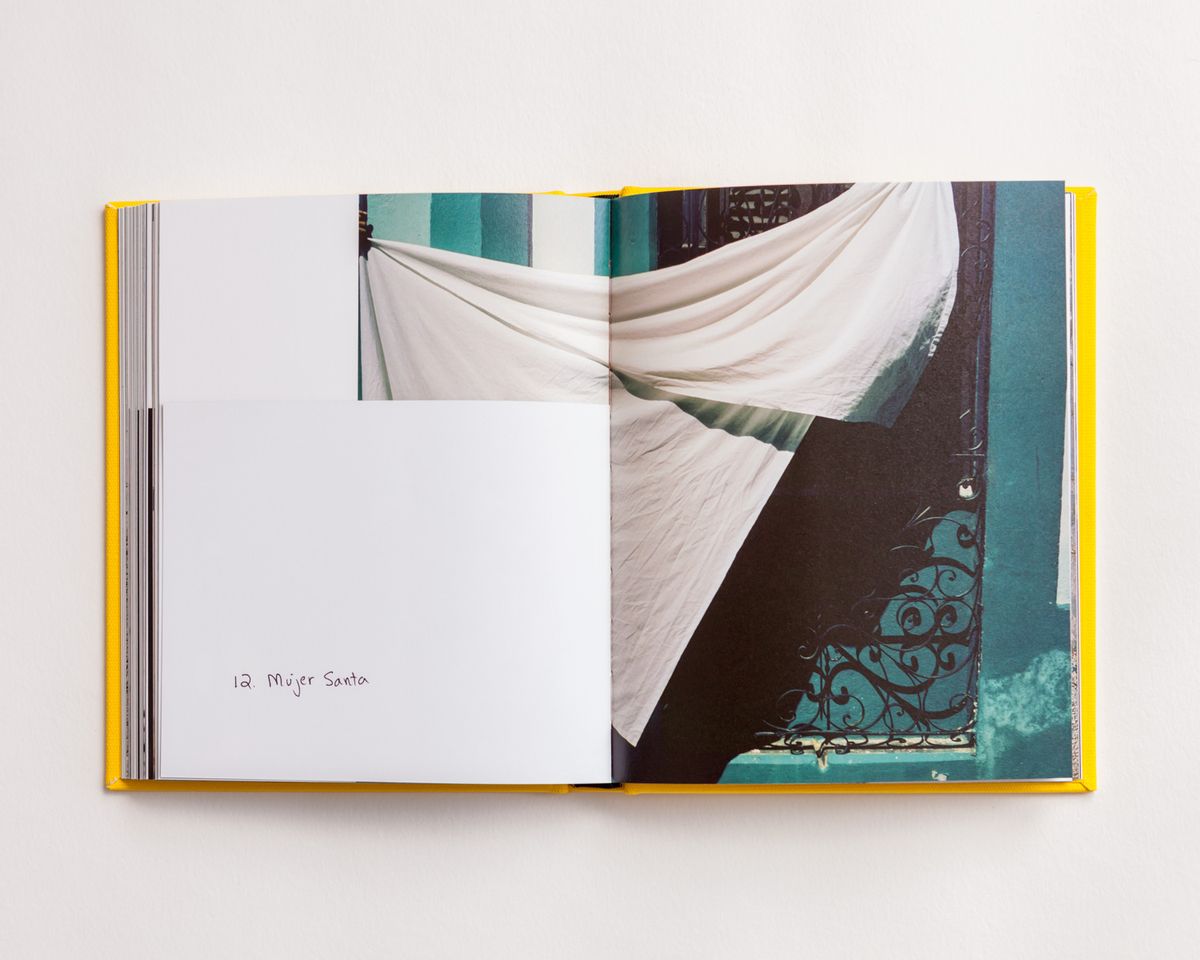

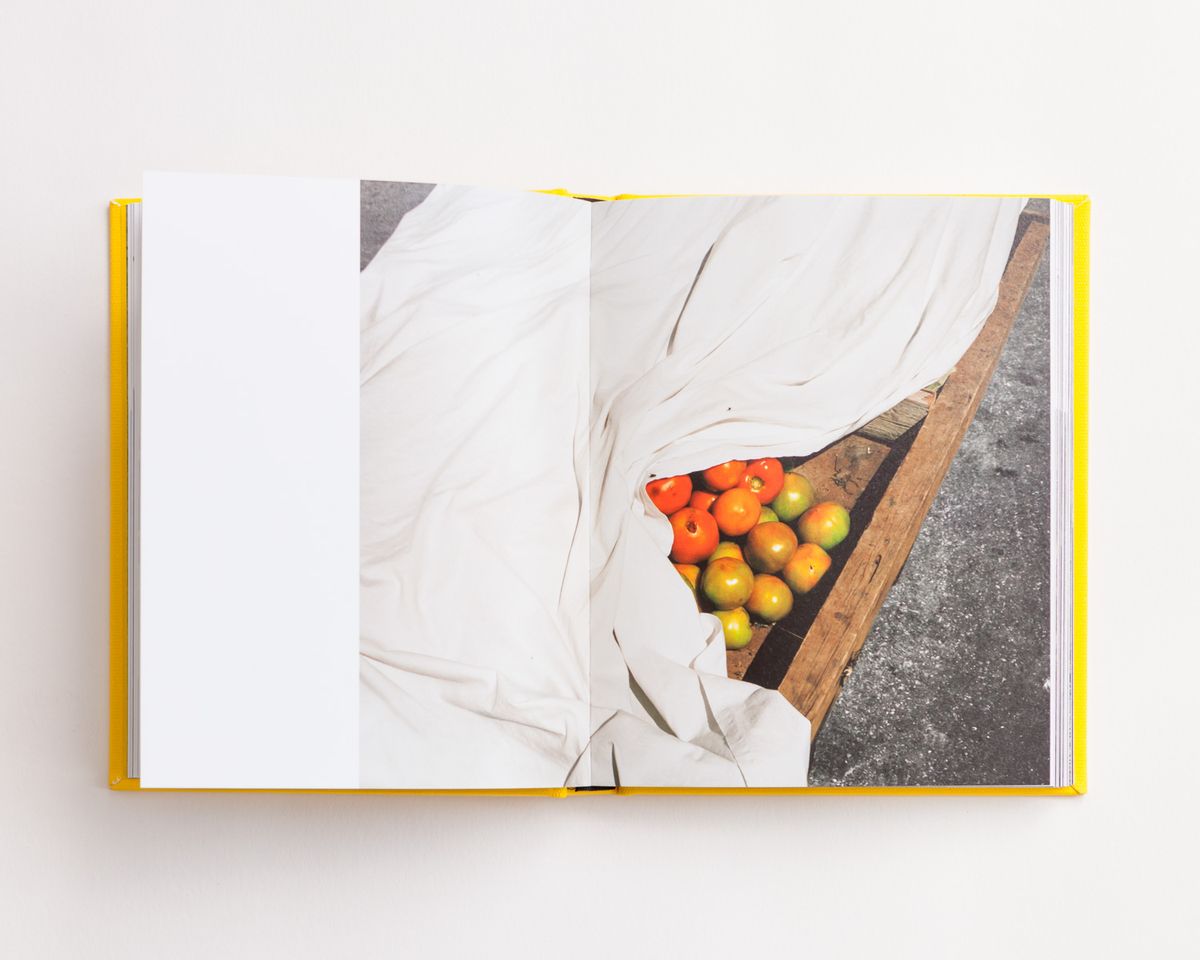

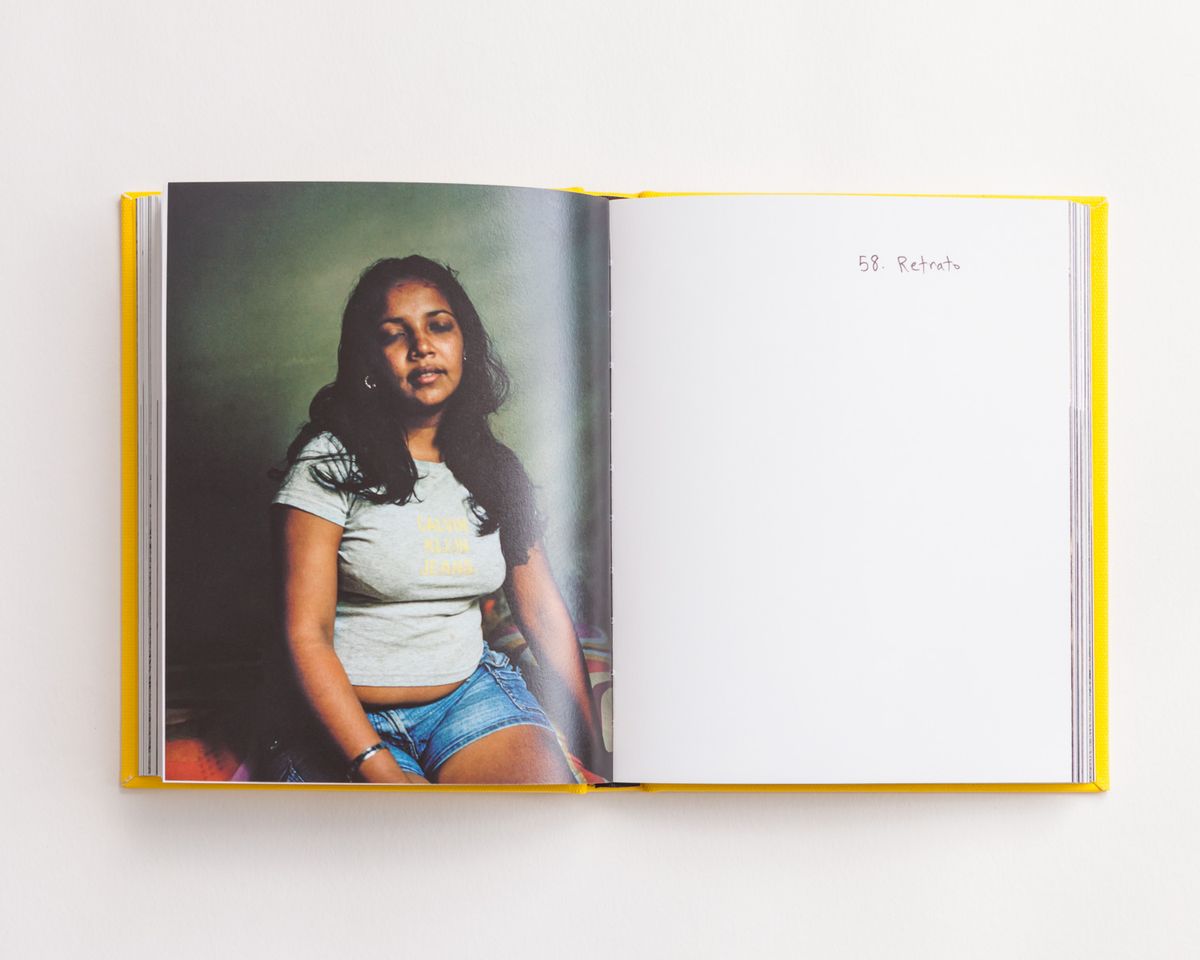

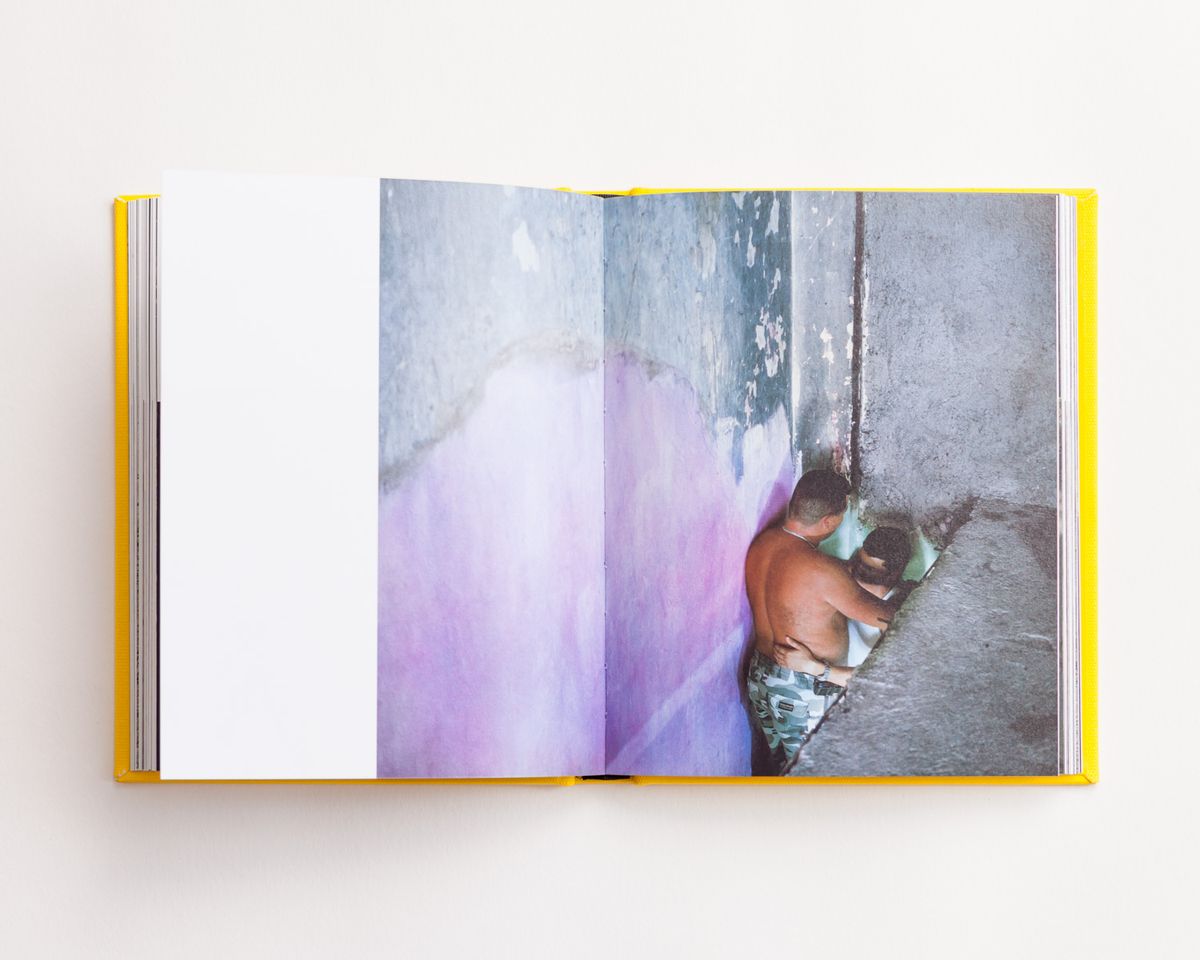

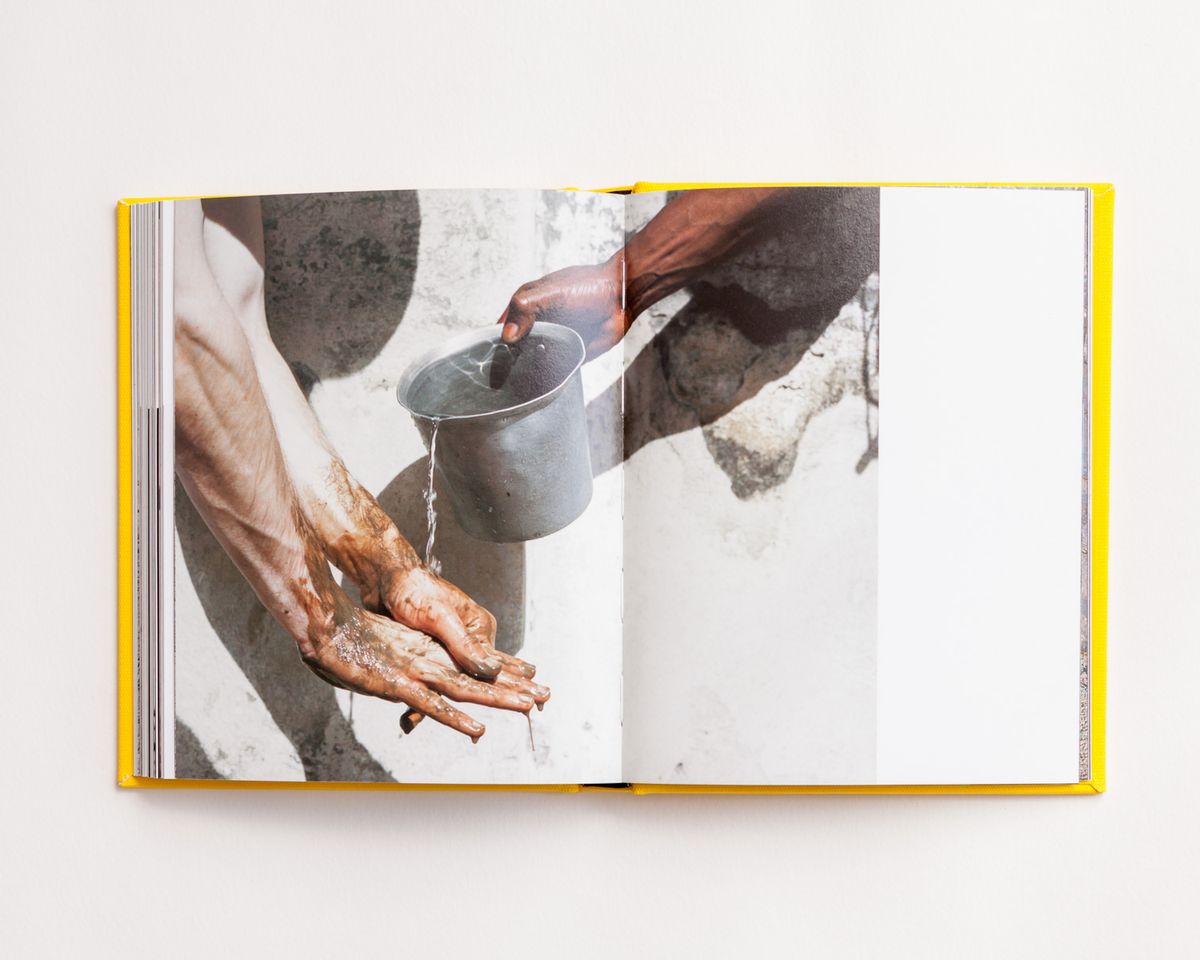

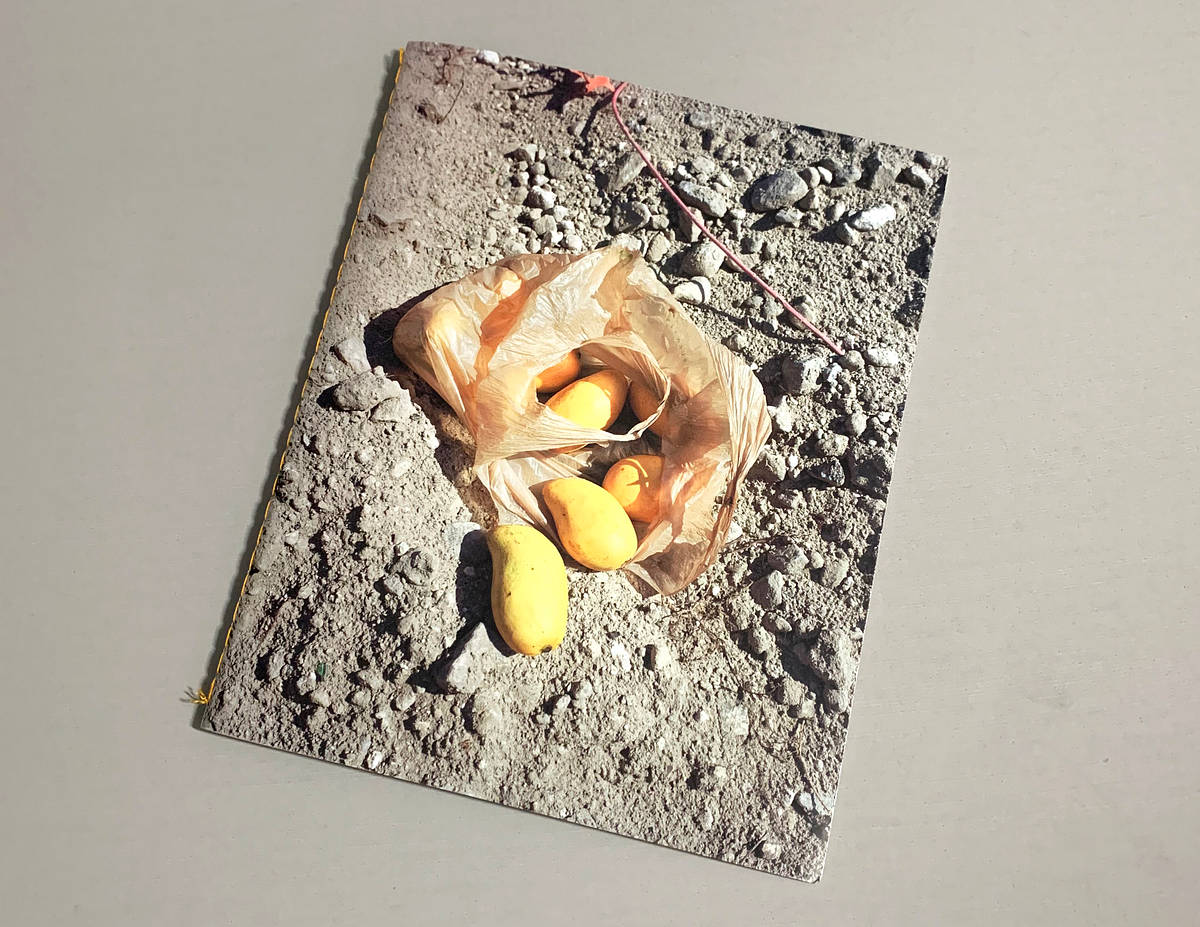

Made over the course of eight years in and around Havana, Rose Marie Cromwell’s El Libro Supremo de la Suerte is an exploration of complex subjectivity and a reflection of her own and her subjects’ relation to place, history, and spirituality. With the photogenic capital as backdrop, it’s the Cubans with whom Cromwell established relationships who take center stage. Well, it’s Cubans and their luck. The series title refers to la charada, the product of Chinese-Cuban syncretism that inventories everyday objects and experiences—83 is “daily problems,” 93 stands for “revolution,” 1 corresponds to “horse.” Because la charada dictates what numbers to play in the local, underground lottery system (which, in turn, is keyed to numbers drawn in Miami), it exists at the intersection of global forces and in the overlap between the spiritual and the every-day life. Not unlike a camera, it functions as a filter: it suggests signals that an encounter with a rope of garlic, a horse, or someone cutting hair, could carry the promise of sudden fortune.

In a country where necessity has driven an underground economy for so many things, from chicken and shoes to hard-drives filled with parts of the internet, the notion of luck isn’t an innocuous one. The lottery system is part of the larger economy of resolver, or making do, when faced with various forms of scarcity brought on by geopolitical forces. And yet, Cromwell’s photographs highlight not what’s lacking but point towards elements of abundance: spirituality, poetry in the everyday, and a palpable sense of openness and community. In exploring the visual connections between numbers—exact and absolute units of measurements—and the mystical, wayward ways of luck, as embodied by locals performing for her camera, Cromwell offers an homage to the people she encountered and a distinctive place that continues to defy expectations and interpretations.

Paula Kupfer